I never, and I mean never, watch The Today Show or Good Morning America.

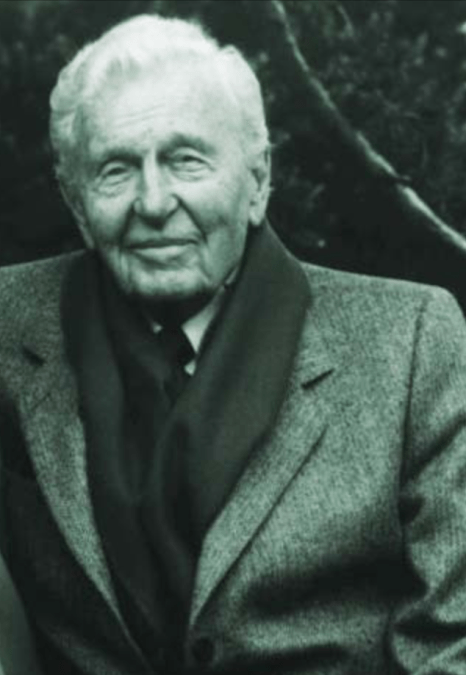

CBS and ESPN are my drugs of choice. But my husband left NBC on from the night before, and BAM. When I turned on the TV the next morning, . Henry Winkler ! His inviting face, that great, thick, white hair, and his warm smile made my lackluster morning warm to the touch. He transported me back to 1994.

—-

I had just moved to Cincinnati, Ohio with my husband and children. This LA Woman and transplanted New Yorker did not take kindly to the idea of the Midwest. I balked. I bellowed. I pushed my face to the glass of the jet as it took off out of LaGuardia in a thunderstorm. But tears of abandonment dried up in an instant as the Queen City came into view. It glittered in the dusk like a tiny jewel box.

“This looks like Downtown LA,” I said to my husband.

I had, in a back ass way, gone full circle – from Beverly HIlls’ Rodeo Drive to Cincinnati’s Burley Hills Drive.

For the first time, I felt at home. I dug into our gracious old colonial while my husband hit the corporate world. As an executive, he was expected to join many boards. He loved all of the organizations he supported, but he took a particular shining to his role at the Springer School – one of the finest primary schools in the country for children with learning disabilities.

In 2004, he suggested I help with the school’s fundraising committee. And, initially, I demurred. I’m just not a joiner. I was kicked out of the Brownies as a kid, I dissed the fifth grade Glee Club, and I gave the Junior League a valiant attempt, but the conservative, knee-length dresses and pearls. I’ve always been a proverbial stranger in a strange land.

But, I am also a champion for kids, and I too struggle with a bag full of learning issues. So I finally jumped into the event.

By the time I saddled up to the The Committee table that Fall, the ladies were already deep in the throes of planning the annual fundraising gala. One woman tossed out her wild idea to book Henry Winkler as the keynote. After all, he had just finished his children’s book series, Hank Zipzer, about a young boy with dyslexia.

My Hollywood wheels began to spin.

“I can get Winkler,” I blurted. All ears perked up.

It was bold move. I didn’t know him. I’d never met him. I’d just watched him on TV same as everyone else. But I had chutzpah.

“HOW?” They all seemed to say with their eyes.

“I’ll find out who is agent is.”

What the hell had I just done? Promised magic I couldn’t produce?

I raced home feeling simultaneously high and low. Why did I have to go strutting my, “I’m from Beverly Hills. I’m connected,” stuff with these nice women? I had to deliver.

So I ran upstairs and googled Winker’s talent agency. Bingo. His number popped up, and I dialed the digits. I’d worked in and around the biz long enough to know I ‘give good phone.’ So when an assistant picked up, I went into my rap. Within a minute, she connected me to his speaking agent. I managed to break her rough ice, spill the particulars of the school and event, and cordially invite him to share his story. Then I held my breath.

“Mr. Winkler would be honored. But if you mention, advertise or display ‘The Fonz’ or ‘Happy Days’ during the event, he will not come.”

AGREED.

I. Was. Elated. Success had a five-star ring to it.

Henry arrived for his big day on a bone chilling mid-March morning. Arrangements had been made for him to stay at the Hilton Netherland Hotel, where the event would also be held. I greeted his limo, and we exchanged huge smiles. We raced up to his room, hung up his suit for the evening and jumped back in the car to meet the children waiting to greet him.

Talk about a warm reception. It was deafening. Kids filled the indoor gym, clutching their copies of Hank Zipzer. They’d all read more than one in the series, word-for-word. They screamed. And yelled. And exploded with such joy, Henry was simply bowled over. He stood amongst them, quieted their squealing and began to speak. I have rarely been in the presence of an actor, or a man, who was as genuine and captivated with children. I literally had to drag him out of the room, to make it to the fundraiser. I was more than sure he would have stayed and hung out there all night if I let him.

At 6 PM, a record 450 guests began to arrive. The Hall of Mirrors was set. HERE’S TO HENRY was about to begin. Henry took his seat next to me, and he barely said a word throughout dinner. He simply watched and listened as guests chattered over other speakers. At one point, henry turned to me, held my arm and whispered, “are they going to be this rude with me too?”

As guests finished dessert, Henry stepped on stage and silenced the crowd. For forty minutes, no one so much as sneezed as he delivered a breathtaking event without a note. Or teleprompter. Or a prepared speech. Most of the audience was not aware, nor was I, of his own learning disabilities. That’s what inspired him to write the Hank Zipper series. But not before struggling through school to eventually graduate from Yale.

Did he speak of the Fonz? Not once. Or Happy Days? No way.

He simply looked out at the crowd, took a deep breath and said, “Thank you for listening, my parents never did.”

Before he left to catch his redeye back to L.A., Henry waded through the crowd to say goodbye. He couldn’t get a word in before I hugged him.

“Thank YOU. My parents didn’t listen either.”

And thank you, Hoda and Kathie Lee, for taking me back.

But I’ll be returning to my regularly scheduled programming tomorrow morning.

Jack Nicholson came to my 18th birthday party. And no one spoke with him.

Jack Nicholson came to my 18th birthday party. And no one spoke with him.